Summary: A nuanced and detailed biography of a woman that has primarily been reduced to a single act.

Summary: A nuanced and detailed biography of a woman that has primarily been reduced to a single act.

I have read Jeanne Theoharis’ books out of order. Her more recent book, A More Beautiful and Terrible History: The Uses and Misuses of Civil Rights History, has many themes hinted at in The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks but more fully fleshed out in the second book. Both books are well worth reading, although there is some overlap. There is a running joke among Civil Rights historians that quite often, the history of the civil rights moment is presented as that one day the Supreme Court announced the end of school segregation, and then the next day Rosa Parks sat down. A day later, MLK stood up to give his I Have a Dream Speech. Then the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the Fair Housing Act of 1968 were passed, and MLK was assassinated. The real history of the Civil Rights Movement is much more complicated and much longer.

In some ways, it is hard to categorize the boundaries of the movement because, as with all history, events influence other events. Both The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks and At the Dark End of the Street: Black Women, Rape and Resistance-a New History of the Civil Rights Movement from Rosa Parks to the Rise of Black Power emphasize that by 1955, Rosa Parks had been participating or leading on civil rights issues for nearly 20 years. The December 1, 1955 events may not have been explicitly planned as an NAACP action, but it was not a random event that did not have a larger context. Several events had to work together. Rosa Parks tended to avoid James Blake’s bus because she had had run-ins with the bus driver before. Other events around the country like the lynching of Emmett Till, the Interstate Commerce Commission’s ruling banning “separate but equal” regarding interstate bus travel, and Rosa Parks’ recent participation in the Highlander Folk School training all likely had some effect. In the end, Rosa Parks refused to get up from her seat. City policy should have meant that she did not have to move because no other seats were available. Instead, the bus driver called the police, and she was arrested. Because this is such an essential part of Rosa Parks’ legacy, the event and the bus boycott are significant parts of the biography. But the biography also clarifies that Rosa Parks was far more important than just her single act, even if that act is what she is known for.

The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks and many other books about less well-known figures of the Civil Rights movement show the considerable cost that everyday people suffered. Money is not everything, but it is one illustration. According to tax records, it took ten years for the couple to recover their income from before the bus boycott, and they were not a wealthy family. At the low point, their income was cut by 80%. Even so, during this time, they were forced to move to Detroit to escape the harassment and job discrimination once the boycott was completed. Rosa Parks spent nearly two years working as a receptionist at the Hampton Institute in Virginia (a historically black college) away from her husband and mother because it was the only job she could find (and the Hampton Institute did not provide housing for the whole family). It was not until a year after the newly elected congressman John Conyers hired her as a congressional staffer in 1965 that their income reached above the pre-1956 income.

As always, there are details that I learn from every book. One of the things that was made evident in The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks, in the context of voting rights, is that not only were potential Black voters given personalized “literacy tests” that were not given to potential White voters (because of grandfather clauses), but when a Black person was attempting to register, they had to pay not just a poll tax for the year that they were registering, but back taxes for every year that they had been theoretically eligible to vote. And again, in many cases, White voters were exempted from the poll taxes in the authorizing legislation. Rosa Parks attempted to register to vote three times. The first time she failed the literacy test. The second time she passed the literacy test but was never mailed a voting card (white voters were given the card at the time of registration, but black voters were mailed their cards.) The third time she again passed the literacy test but had to pay the annual poll tax of $1.50, but for all eleven years that she was technically old enough to vote. This would be the equivalent of nearly $300 in 2022 dollars, not an insurmountable amount, but when she and her husband’s combined income would have been about $60-75 a week, it was still a significant sum. Rosa Parks’ husband could never register to vote until they moved to Detroit in 1956.

One of the book’s themes is the tension between respectability politics and the very real backlash against civil rights organizing. Rosa Parks was known for her conservative dress and proper manners. She was also a woman of deep faith and humility who did not like to promote herself or her needs. That conservative dress did not mean that she was politically conservative. In her later years, she spoke at the Million Men March organized by Louis Farrakhan and the Nation of Islam. She regularly attended meetings for the local chapter of the Black Panthers in Detroit. But Parks was aware of respectability’s role in the civil rights movement.

The paradox was this: Parks’s refusal to get up from her seat and the community outrage around her arrest were rooted in her long history of political involvement and their trust in her. However, this same political history got pushed to the background to further the public image of the boycott. Parks had a more extensive and progressive political background than many of the boycott leaders; many people probably didn’t know she had been to Highlander, and some would have been uncomfortable with her ties to leftist organizers. Rosa Parks proved an ideal person around which a boycott could coalesce, but it demanded publicizing a strategic image of her. Describing Parks as “not a disturbing factor,” Dr. King would note her stellar character at the first mass meeting in Montgomery, referring to the “boundless outreach of her integrity, the height of her character.”

The foregrounding of Parks’s respectability–of her being a good Christian woman and tired seamstress–proved pivotal to the success of the boycott because it helped to deflect Cold War suspicions about grassroots militancy. Rumors immediately arose within white Montgomery circles that Parks was an NCAAP plant. Indeed, if the myth of Parks put forth by many in the black community was that she was a simple Christian seamstress, the myth most commonly put forth by Montgomery’s white community was that the NAACP (in league with the Communist Party) had orchestrated the whole thing.” (p83)

Rosa Parks immediately resigned her membership in the NAACP after the arrest. And that part of the process was not incidental to the larger boycott. The Alabama Attorney General got a court order banning the NAACP in June 1956 after attempting to prosecute the leaders of the boycott for conspiracy in March 1956. Within weeks of the start of the boycott, Rosa Parks was fired from her job (the whole department was closed within the department store she worked at), and her husband was pushed out of a job as a barber on a local Air Force base, which was technically desegregated already. Part of Parks’ reluctance to assert herself is that she worked to care for others but did not like expressing needs. That, combined with the sexism of the early civil rights movement, meant that others were supported, but she was not. The Women’s Political Council organized the initial boycott under the leadership of Jo Ann Robinson. Still, the initial meetings of what became the MIA (Montgomery Improvement Association) excluded both Jo Ann Robinson and Rosa Parks. Rosa Parks was not allowed to speak at the first mass meeting even though he had a history of speaking at civil rights events organized by the NAACP and had led youth organizing for years. Women primarily staffed the boycott as drivers and operators, and it was primarily women who were the riders doing the boycott. But it was a male leadership that claimed authority. Rosa Parks was not even invited to a number of the initial commemorations of the Montgomery Boycott or the Southern Christian Leadership Council. Although she was regularly asked to speak at fundraisers, she spent much of the year during the boycott traveling to speak at fundraising events, mostly without being paid for her time.

As was highlighted more with Beautiful and Terrible History, the sexism of the civil rights movement increasingly mattered over time. The 1963 March, which very clearly marginalized women and in which Rosa Parks spoke eight words, was the start of women refusing to allow their role to be marginalized when they were the ones that were so often responsible for so much of the mundane work.

The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks plays a similar role to The Radical King. Both King and Parks and many others have been remaindered for a small part of what they did. Their work and thought were flattened. King’s change happened after his death. But Parks’ misremembered history and her reduced role were both a necessary feature of the Montgomery boycott because of the reality of the racism at the time, and a feature of sexism of the movement. Rosa Parks’ may bear some responsibility because of her humility and reluctance to assert a public role. But her history as an organizer and her willingness to speak and act throughout the rest of her life in public and often dangerous ways shows that the resultant to assert a public role did not mean that she was trying to hide. She was not trying to assert leadership competitively. And she was not trying to make her (very real financial and other) needs more important than the genuine financial and other needs of other people around her.

The more I read, the more I think the stories of lesser-known figures, especially women leaders of the Civil Rights Movement, need to be told. I do not know if I would recommend The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks or A Beautiful and Terrible History to be read first. A Beautiful and Terrible History is a bit shorter and covers more topics. But many of the topics, the marginalization of women, the under-appreciated reality of northern racism during the Civil Rights Era, the longer history of the movement than what is often appreciated, the problems of the white moderate and of media, the role of young people and of broader social issues in the US and globally, and the role of historical memory are all topics that both books cover even if they cover them in slightly different ways. Rosa Parks plays a significant role in both books, and both are books that should be more widely read. You cannot go wrong with whichever one you start with.

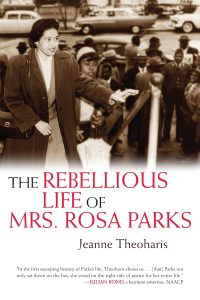

The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks by Jeanne Theoharis Purchase Links: Paperback, Kindle Edition, Audible.com Audiobook