Summary: If we want to address the crisis of loneliness and the lack of community in American society, we need to learn how to listen and know others.

Summary: If we want to address the crisis of loneliness and the lack of community in American society, we need to learn how to listen and know others.

Both of David Brooks’ last two books I had decided not to read, and then I changed my mind once I read reviews of them. But both of them had significant weaknesses, and Brooks was not yet ready to write either book. He wrote the books because he was an author and because writing and research are part of how he processes his own issues. He published because he was on deadline, not because he was really finished processing them. Because of this history, I again did not intend to pick up How to Know a Person. But again, I was drawn to them because of two podcasts. Curt Thompson interviewed him on Faith Angle. And then, more personally, he was interviewed by his real-life friend Kate Bowler on her podcast Everything Happens. These are very different podcasts. Curt Thompson is a Psychiatrist who has written about spiritual formation, the soul, shame, and neuroscience. That conversation is more about the technical issues of friendship, what relationships do for us, and why we need them. But it is easy to tell that Kate and David are not just acquaintances but actual friends who really do get together regularly. They talked about calling one another and going over to each other’s homes to talk when needed. And that very personal conversation showed the aspect of how David has put into practice what he has been writing about for the past decade. That “putting into practice what he has been learning” which made me want to pick up How to Know a Person.

How to Know a Person has a mix of scientific research about how to listen, seek out friends, and why that is important. But the emotional center of the book is the three chapters telling the story of the suicide of David’s oldest friend a few years ago. The main chapter is a revision of an essay he wrote not too long after the suicide. He grappled with that suicide and told the story of his friend’s depression and how he tried to help. The two additional chapters are about what he learned afterward about depression and suicide and what advice he would have now for those who are either grappling with depression and suicide or those who have loved ones who are. All of these chapters are well-written, careful, and helpful. There is no silver bullet, but some things may be helpful.

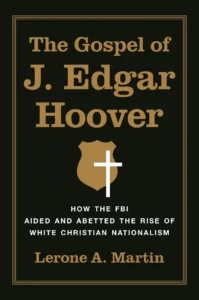

Summary: J. Edgar Hoover’s understanding of Christianity significantly influenced his management of the FBI, and in turn, the FBI impacted the broader development of what has become the Christian Nationalist movement in a modern sense.

Summary: J. Edgar Hoover’s understanding of Christianity significantly influenced his management of the FBI, and in turn, the FBI impacted the broader development of what has become the Christian Nationalist movement in a modern sense.