Summary: Exploration of spiritual disciplines from 20th century mystic Howard Thurman.

Summary: Exploration of spiritual disciplines from 20th century mystic Howard Thurman.

At the end of June I did a 8 day silent retreat with Jesuit Antiracist Sodality (JARS) at Ignatius House. As I have described it to others, it was the least silent, silent retreat I have done. That is not to say it wasn’t a silent retreat, but that it had more “content” than a standard retreat because it was themed. Each day there were three times of worship, a Morning Prayer service where the “witness of the day” had a passage read by or about them and there was a sermon. And then on the way out of this service, we would be given a guiding sheet about the witness of the day that had links to an audio or video or a written passage. Usually there was also a couple of songs that matched the theme and some directing questions to prompt reflection. Unlike the previous two silent retreats I have done, there was full music at every service, mostly gospel or spirituals with sung psalms and mass elements. Then just before lunch there was a full mass and Eucharist with another sermon and more music. This service sometimes went for 90 minutes. And then there was an evening service that included music again, but was primarily focused around a prayer of examen.

Also unusual for a silent retreat, there was an optional hour before dinner where people could come to debrief. And five of the nights had some type of video that we watched together, mostly documentaries. It was still a silent retreat, but there was more directed content than a usual silent retreat and there was both a good bit of singing and time for discussion in addition to a normal daily meeting with a spiritual direction (which we still had.)

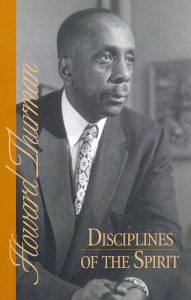

Disciplines of the Spirit was the book that I slowly read over the week. It is a short book, only about 130 pages. There were five chapters. I am strongly influenced by Howard Thurman, but I do not universally love everything that he writes. I am frequently frustrated by some of the modernism of his approach or his theology. And he was writing mostly in the 1940-1970s, prior to the rise of Black Liberation theology and the Womanist critique of the early liberation theology.

The book starts with two chapters on commitment and growth. Overly simplistically, Thurman advocates for a deep commitment as part of our commitment to the spirit. And he has a full chapter to discuss the need for growth by looking at Jesus’ need for growth. If Jesus is a model for us (he is not only a model theologically, but being a model human is part of what Jesus is for us), then if Jesus needed to grow “in wisdom and stature” we should also expect that we need to growth. These two disciplines are essential to the last three disciplines.

The third chapter is a discussion of suffering as a discipline. The chapter on suffering is a backward response to the problem of evil. I think that is helpful reframing of the problem of evil by looking at freedom as a necessary part of love. If God is a god of love, then we have to have freedom to respond to that love. A byproduct of freedom is the possibility of failure and suffering. In this framing, freedom that does not have the possibility of failure and suffering would not really be free. I think there are some weaknesses to this approach if you press into it, but as a brief approach I think it is helpful. This is not unlike what I have heard from others about the necessity of struggle to achieve growth. A toddler cannot learn to walk without falling. Falling is part of how a child learns balance. And children start with rolling, standing and crawling to learn movement before walking. Falling is not itself a wrong that should always be avoided. If we avoid all falling, then we would as a result avoid the end result of walking.

As I hinted at above, I think that the womanist critique of viewing meritorious suffering as an unalloyed good is an appropriate critique of the chapter even as I largely agree with Thurman’s approach here. I think if Thurman were writing later, he would have written this chapter (and the rest of the book) differently in response to not only the womanist critique around suffering, but in other matters like his use of masculine language to be universal. So while I don’t love the idea of suffering being a “spiritual discipline,” I do think that his framing of how suffering and struggle is part of the spiritual life is right.

The chapter on prayer is seemingly simple in comparison to the other chapters. Without mentioning it, Thurman seems to be drawing on the understanding of prayer that is in The Cloud of Unknowing. Maybe there is an independent Quaker source that is similar that he is drawing on instead. Thurman has the combination of mysticism and modernism that I think can be a bit opaque at times. But this seem clearer to me what come other areas.

Prayer is communication. The key to communicating with God is to be on the same wavelength. Silence is key to getting on the same wavelength with God. Spiritual Disciplines are the work to remove that which keeps us from God. When we have the hunger that God plants in us become the dominant desire, then we are ready to pray. In the Ignatian sense this is detachment. Thurman tells a story of a woman expressing to God all of her memories and feelings about a question before her, and at the end, she has this sense of openness to all options because she has opened herself to God and she trusts in him.

I have some issues with thinking about prayer this way. Because I am not sure that detachment is right, it feels too much like Greek philosophy that suggests that emotion is a problem. But Thurman isn’t quite saying this. He includes feelings and emotion as being essential to prayer. So I think it is that once those have been communicated, then we have to trust God. I think Ignatius had a different conception that he had to come to a place of acceptance and detachment from wanting a particular solution. Thurman is similar but slightly different in that he isn’t saying to not want the solution that you want, but that once you have communicated it to God, then our role is to trust.

Later in the chapter there is a good section on confession. He is suggesting that we have an innate need within us to confess our sin before God. Once we have laid bare our reality and properly acknowledged our role, then we can come away without guilt and know that our sin is forgiven and we are wholly known by God and loved. And while that does not mean that the impact of our sin is completely gone, Thurman says that in a way we can’t fully know, that it is like ‘a solvent’ begins to work on our sin so that we will move toward total healing.

Again, I don’t think that Thurman would say that this is all that needs to happen. There is a role for human restitution and repair for the impacts of sin. But what he is talking about here is the way that sin binds us internally and harms our soul. It isn’t that God can stop loving us or that we can’t pray as a result of God’s withdrawal from us, but that our own internal make up is harmed by sin and that confession is part of the process of these repair.

The final chapter is on the discipline of reconciliation. My comments here are already too long so I won’t spend too much time in this chapter, but I do want to note that the last five pages of the book are some of the best and most important writing on the concept of love that I have ever read. I would quote all of it if I could. Overly simplistically, these pages suggest that after everything that has come before, love is the true center. This is a long but beautiful quote:

“Every man [one] wants to be cared for, to be sustained by the assurance of watchful and thoughtful attention of others.” Such is the meaning of love.

Sometimes the radiance of love is so soft and gentle that the individual sees himself with all harsh lines wiped away and all limitations blended with his strengths in so happy a combination that strength seems to be everywhere and weakness is nowhere to be found. This is a part of the magic, the spell of love. Sometimes its radiance kindles old fires that have long since grown cold from the neglect of despair, or new fires are kindled by a hope born full-blown without beginning and without end. Sometimes the same radiance blesses a life with a vision of its possibilities never before dreamed of or sought, stimulating new endeavor and summoning all latent powers to energize the life at its inmost core.

But there are other ways by which love works its perfect work. There is a steady anxiety that surrounds man’s experience of love. It may stab the spirit by calling forth a bitter, scathing self-judgment. The heights to which it calls may seem so high that all incentive is lost and the individual is stricken with utter hopelessness and despair. It may throw in relief old and forgotten weaknesses to which one has made the adjustment of acceptance—but which now stir in their place to offer themselves as testimony of one’s unworthiness and to challenge the love with their embarrassing reality. At such times one expects love to be dimmed, in the mistaken notion that it is ultimately based upon merit and worth.

Behold the miracle! Love has no awareness of merit or demerit; it has no scale by which its portion may be weighed or measured. It does not seek to balance giving and receiving. Love loves; this is its nature.

This goes on for pages about the role of love and the importance of being seen and rooting that love in God. He returns again, like in his sermon The Sound of the Genuine to Psalm 139. We can love because God has loved us and will not leave us. And we can love others out of gratitude for that love.

Thurman notes that we can want this type of love from others, but then not be willing to give it to others. God can empower us to love in this way if we ask and most often we get to love another this way by seeking to understand the other. Generally, we have to condition ourselves to have leisure (or at least appear to have leisure) to love others so that we are joyful to listen to others and truly know them.

I wish Thurman were a bit easier for me to read. I tend to get bogged down in his reading and it is really someplace like a silent retreat where I can read longer works by him. I didn’t have any problem reading his autobiography. And I like his sermons and short devotional writing, but I never seem to finish collections of those. I think I am going to read his book on the spirituals next. I am about finished with a collection of essays about Thurman. And I want to pick up Howard Thurman: The Mystic as Prophet by Luther Smith at some point this year.

Disciplines of the Spirit by Howard Thurman Purchase Links: Paperback