Summary: An exploration of what could have been had evangelical history gone other ways.

Summary: An exploration of what could have been had evangelical history gone other ways.

I have always enjoyed history. But it has mostly been a reading hobby, not something I studied. Over the past decade, I have been more intentional about reading history to fill in gaps in my knowledge, but I have also read more about the study of history. I think it was John Fea’s podcast where I first heard about the 5 Cs of the study of history. Those five Cs are: change over time, causality, context, complexity, and contingency. All five are important to understanding history.

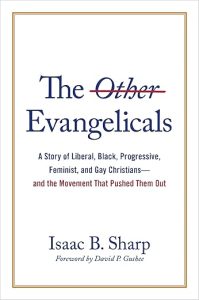

Isaac Sharp’s The Other Evangelicals does approach all five Cs in his exploration of five groups of people who have been marginalized in evangelical history, but in many ways I read this as a book primarily thinking about contingency, the “what could have been” had evangelical history gone other ways.

As with any recent history, my own story influences how I read. I grew up American Baptist. Traditionally American Baptists are considered a mainline denomination and would be included in the “liberal” part of Christianity. I didn’t really understand how liberal the denomination was as I was growing up in part because I was in an evangelical wing of the denomination. I do very much remember going to the only national youth gathering I attended as an American Baptist and one day of the youth conference primarily used feminine references for God. There was no explanation for it and it raised all kinds of questions for other students I was with. I spend a good bit of time that day talking to others about how there were feminine images of God in scripture and how God is not gendered as we traditionally consider gender in humans. I was mostly irritated by the poor presentation, but not at all bothered by the presentation of somewhat liberal theology.

In college I spent a year going to an intentionally interracial church (I only went one year because I didn’t have a car and it was a 35 minute drive into Chicago to go to the church. I never considered going to the Black baptist church that was within walking distance of campus for some reason.) I was aware of the problems of race within evangelicalism during college and explored the development of NBEA and Tom Skinner and John Perkins and other Black leaders within the evangelical world. I was hired to work by the SBC association in Chicago right out of college as I was going to grad school. That association at the time was one of three associations (of about 1200) in the country that was predominately made up of minority churches. I mostly worked with Black churches developing church-based non-profits and spent a lot more time in Black churches, some of whom identified as Evangelical, but most did not.

Part of my grad school was a Masters of Social Service Administration (an administrative focused equivalent to an MSW). I have always been on the progressive side of the evangelical works and have followed the work of Tony Campolo and Ron Sider and others since high school. Social justice and progressive causes were are always a significant focus of my work as a Christian.

It wasn’t until I was in college that I started to understand compmentarianism. The term was only coined a few years before I started college. I knew American Baptists ordained women and that not every evangelical denomination did. But I knew women pastors and just never really considered male only pastorate as a viable option. Another church that I went to for a little while in college was a very conservative church that had a large college contingent. Again, I went in part because I didn’t have a car and friends who did have cars went there. For several months the college ministry Sunday school class studied gender, including why that church was complementarian. I stuck it out through the whole study, but was completely unpersuaded. So I had context for the book in the feminist section as well as the liberal, progressive, and Black evangelicals sections. It was only the history of gay evangelicals that I really had no historical experience with.

One last point, I took two classes with Mark Noll in college and audited another when he was guest lecturer at University of Chicago Divinity School. Noll’s approach to rooting mid 20th century neo-evangelicals as part of a longer tradition of evangelical Protestants was my dominate way of thinking of evangelicalism until fairly recently. Matthew Avery Sutton’s essay about evangelical historiography gave language to not just my concern about the use and definition of evangelical, but also to the method of thinking about evangelicalism as historically rooted group of people that arose out of the English reformation. I still strongly appreciate Noll, Marsden and other evangelical historians, but I am now going be reading their history with more nuance than I did previously. That is a very long introduction to a fairly straight forward book.

The Other Evangelicals looks at the history of the Evangelical movement that arose in the late 1940s and early 1950s and the ways that his five areas of self-identified evangelicals who were liberal, progressive, Black, feminist and gay. In most of these sections there were fairly clear lines of who was in and who was out regardless of self-identification. In the chapter on liberal evangelicals, the main focus was on biblical studies and the fight over inerrancy. The Chicago Statement on Inerrancy was not the first fight to define what an Evangelical understanding of the Bible was, but by the time it was written in the late 1970s, it was clear that there was little tolerance for a more liberal stream of evangelicals who were less concerned with plenary inspiration and an error free bible.

The main illustration in the liberal chapter was Bela Vassady, a Hungarian WWII refugee who was one of the early professors at Fuller Seminary starting in 1949. Vassady was a European who identified as evangelical, but his stream of evangelicalism did not match up with Fuller’s understanding of biblical orthodoxy because he was too sympathetic to Barth and did not reject German methods of biblical theology outright. Vassady had helped to found the World Council of Churches and understood his role to be ecumenical. The story of opposition to Vassady was a good reminder that Christian colleges and seminaries have been accused of being “liberal” for a very long time. The influence of donors concerned about the mission of school and liberal drift has always been present.

The chapter of Black Evangelicals I think was important (although not new by any means) because evangelicals tend to think of themselves as theologically defined. The traditional definitions of evangelical by NAE or Bebbington are rooted in theological statements. But the chapter on Black Evangelicals makes clear that theology was never enough. Billy Graham opposed the methods of the civil rights movement, speaking against the 1963 March on Washington and MLK Jr explicitly on a number of occasions. Sharp quotes Graham, “There is only one possible solution to the race problem and that is vital personal experience with Jesus Christ on the part of both races…any man who has a genuine conversion experience will find his racial attitudes greatly changed.” (p127)

While the chapter on Black evangelicals includes a variety of people, the story is often similar to William Bentley’s. Evangelicalism was a theological tradition that took scripture seriously and at least claimed to value intellectually serious study. Bentley was exposed to white evangelicalism in the 1940s and was attracted to the theology, but was concerned that it “..could be doctrinally correct and, at the same time, hold backward attitudes toward such and important issue as race in America.” Bentley evangelically formed the National Black Evangelical Association in 1963 at a time when Wheaton and many other evangelical schools officially or unofficially still prohibited interracial dating on campus.

Much of the tension beyond explicit racism was rooted in different approaches toward evangelism and ministry. While many members of the NBEA agreed with Graham about the priority of personal conversion as the main method of solving social issues, the Black church historically had been more open to social action as a legitimate role of the church. (Although the National Baptist and the Progressive Baptists split in the 1960s along similar lines.)

The issues raised by Black evangelicals were not confined to just Black evangelicals, white progressives evangelicals also pushed the broader evangelical movement to think more clearly about social action as a role of the church. The 1960s protest movements, racism, war, and poverty were driving forces for progressive evangelicals who championed the working in marginalized communities as a central role of the church. But as the chapter concluded, the requirement for theological conservatism and the social requirement for individualism in approaching social issues like race, meant that progressive evangelicals had an uphill battle to draw attention to social conditions and social ministries that addressed the systemic causes of social problems.

The feminist story of evangelicalism is often assumed to be different than the actual history. The term complementarian wasn’t coined until 1988. While evangelicals were socially and theologically conservative, there were hundreds of women ordained within the SBC in the 1970 and the later orientation toward conservative gender roles was really a backlash to an earlier egalitarian movement.

Again, the concluding chapter on gay evangelicals prioritizes how evangelicals handling of scripture led to the cracks in the approach toward gay evangelicals. In many cases, those who were more inclusive rooted their inclusion on their reading of scripture. There was also a pragmatism that came to the fore as it became clear that changing orientation was not easy.

One of the problems of evangelicalism is a lack of imagination for any other contingency. In many cases, there are and have been many other paths that have been explored, but without knowledge of those paths, it is difficult to not make some of the same mistakes that have already been made.

The Other Evangelicals is very readable history. It is a history that I both knew a lot about but also had details and streams of evangelicalism that I was completely unaware of. I have been skeptical of the label evangelical since the early 90s when I was at Wheaton. The theological definitions of evangelicalism always seem to be less important than the social or cultural identity. The Other Evangelicals was far less political than I thought it would be. The progressive and liberal chapters were more about approach than particular content. And the chapters about feminists and gay evangelicals while they were more about content of those two areas again, came down to largely being about approach.

Evangelicalism grew out of a desire to be less fundamentalist than the early 20th century fundamentalism, but in many ways the evangelical movement never had a full break from fundamentalism. As fundamentalists of the early 20th century became less comfortable self identifying as fundamentalists and increasingly used the term evangelical, the fight over the approach that evangelicalism has toward culture has continued to be largely the same fight.

The Other Evangelicals: A Story of Liberal, Black, Progressive, Feminist, and Gay Christians―and the Movement That Pushed Them Out by Isaac B Sharp Purchase Links: Paperback, Kindle Edition

1 thought on “The Other Evangelicals: A Story of Liberal, Black, Progressive, Feminist, and Gay Christians―and the Movement That Pushed Them Out by Isaac B Sharp”