Summary: The history of the Black Power movement is the lesser-known story of the end of the mid-20th-century civil rights movement.

Summary: The history of the Black Power movement is the lesser-known story of the end of the mid-20th-century civil rights movement.

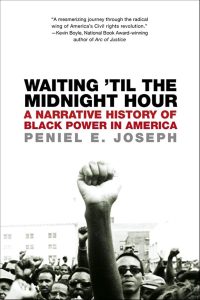

Waiting ‘Til the Midnight Hour is the third book I have read by Peniel Joseph, but it was Joseph’s first book, published in 2006. And as you would expect from an academic historian, his books tend to concentrate on overlapping characters and eras. He is a historian of the mid-20th century civil rights era, concentrating on the Black Power movement. I recommend his biography of Stokley Carmichael and the joint biography of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr.

I purchased the kindle book Waiting ‘Til the Midnight Hour about four years ago but did not get around to reading it until I picked up the audiobook for free as part of the Audible member Plus catalog. The audiobook was not well edited. The narration was fine, but it felt like the editing was not complete. There were many places with long pauses where it appears that the narrator was intentionally putting in a pause for editing purposes that the editor did not remove. And one where the narrator took seven or eight attempts at a name before saying it correctly and naturally in context, and obviously, the editing should have removed that. There were other places where the audio had short repetitions.

Those editing errors (except for the pauses) were all in the book’s first half. So I wonder if the audiobook editing influenced my complaints about the disjointedness of the book’s first part. And that may be the case. But the book felt like it took a while to really come together. The earlier portions of the book were more context of the development of the Black Power movement, which was also the part of the story I was most familiar with. So again, I may have been influenced by being more interested in the later sections of the book, where I was mostly hearing history that I was less familiar with.

I had three main takeaways from the book. First, I think the development of the Black Power movement was significantly influenced by white backlash to the civil rights movement. Stokley Carmichael’s use of Black Power during the 1966 march in Mississippi in response to the James Meredith shooting was not the term’s first use. (Richard Wright had a book in 1954 titled Black Power, and others used the phrase before Carmichael, but it was Carmichael’s use that popularized it.) By 1966, Brown v Board of Ed had been decided 12 years earlier, and much of the country was still segregated. The 1964 Civil Rights act (making it illegal to discriminate on the basis of race in restaurants or hotels, or other public settings) and the 1965 Voting Rights Act had both passed, but the march in Mississippi proved that the federal government was still reluctant to enforce the law. MLK Jr’s assassination less than two years later gave further power to the frustrations of how civil rights were increasingly being thwarted through less overt means.

My second takeaway is that the Black Power movement had some level of sexism within the movement. SNCC, as an organization, identified sexism as a problem within traditional civil rights organizations early on. Ella Baker worked to design SNCC as a more egalitarian organization (both in gender and organizational structure) in response to the more authoritarian and leader-driven organizations like NAACP and SCLC. But as SNCC started to struggle internally, it appeared to become more oriented toward male leadership. Later, groups like the Black Panthers were even more hierarchical, and leaders like Huey Newton and Eldrige Cleaver were accused or convicted of rape. That is not to say that women were not involved in the Black Power movement or that it was an inherently sexist structure, but the sexism that did exist within the Black Power movement influenced the rise of Womanist thought as a reaction. Movements arise not just out of pure ideology but in response to events and as a reaction to earlier lines of thought.

Third, the cultural strength of Black Power as a set of ideals likely has had a more lasting impact than the organizations around the Black Power movement. The Black Panthers were not just about rejecting non-violence as the primary means of achieving civil rights but also about self-empowerment. There was an embrace of radical politics but also conservative ideas as well. And the role of the FBI and the federal and local governments actively planting agents to compromise the group’s organizational structures and to create distrust among leaders played a role in weakening the sustainability of the organizations over the long term.

Cointelpro would eventually include 360 operations designed to disrupt black nationalist organizing and, ultimately, would represent a watershed event in American history as it curtailed the FBI’s long-practiced policy of requiring a connection between domestic dissidents and foreign agents to justify bureau activity. Its secret war against Black Power activists would be marked by unprecedented abuses of federal power that featured the systematic, illegal harassment, imprisonment, and, at times, death, of black militants.

As with much of civil rights history, there has been a flattening of the history of the black power movement until it has become more caricature than nuanced history. Peneil Joseph has helpfully contextualized the black power movement, strengths and weaknesses, to help recover that transitional history from the earlier civil rights movement to the more recent history of a racialized United States.

Waiting ‘Til the Midnight Hour: A Narrative History of Black Power in America by Peniel Joseph Purchase Links: Paperback, Kindle Edition, Audible.com Audiobook