Summary: Discussion of the cultural and real privilege of being a White Christian (or at least conversant in Christianity) in America.

Summary: Discussion of the cultural and real privilege of being a White Christian (or at least conversant in Christianity) in America.

I recently read Taking America Back for God, a book about Christian Nationalism, and when I was writing up my review, one of the books recommended was White Christian Privilege. I did not know anything about the book or author, but it fit in my recent reading, and I picked it up.

The author is a second-generation immigrant from Southeast Asia. She grew up in Atlanta and now is a professor specializing in race and religion. The book’s premise is explained well by the title: religious liberty is illusionary in the US because it is primarily rooted in the freedom to be Christian. White (Protestant) Christians are the default state, and others tend to be religious in relation to Christianity. (Robert Jones’ book The End of White Christian America tells the opposite side of this story.)

White Christian Privilege will not be received well by many who believe that Christianity is under attack or persecuted. And there is some small sense that demographic change is impacting the dominance of White Christians to some extent (the demographic trends are the primary focus of Jones’ book). However, demographics do not show the privilege that Christianity has baked into the United States culture and history.

There are legitimate arguments about whether the US was founded as a ‘Christian country,’ but culturally, Christianity was normative (the default cultural expression.) While there have been Native Americans, Jews, and Muslims from very early in US history, Christianity has been dominant. So, Christian assumptions about how religion works have also been normative. Christian holidays are national holidays (and Hindu holidays are not, and often not even known). A Hindu woman who wants to celebrate Diwali must request time off from work, but Christmas is a national holiday, and the workweek is oriented around the Christian calendar. These assumptions are not consciously chosen or intentionally discriminatory but have an impact. (Similar to how crash test dummies were modeled initially after adult males and only later have changes been made to include women and children when it became clear that the single choice of crash test dummies negatively impacted women and children).

The narration of religious liberty cases from the Supreme Court was particularly striking because I heard several people recently talk about how the Supreme Court has ruled so clearly for religious liberty recently. But the choice of which cases to include as religious liberty cases in those recent articles has been biased toward Christian cases, and religious liberty cases for others were not counted as losses.

One of the striking points here is that recently, there has been a string of complaints about how the courts have narrowed their understanding of what it means to practice faith to explicit worship-based practices, but that is similar to how the Protestant-based Supreme Court of the mid-20th century understood non-Christian religious traditions. Religious obligations like wearing a headscarf (Islam) or not cutting your hair (Sikh) have been considered optional, like wearing a Christian cross necklace instead of a more central feature like taking communion would be for a Christian.

One of the crucial points here is that individual Sikh men would go through lengthy and costly legal battles to be permitted to wear turbans and beards, but there were no policy changes. This would then force other Sikh men to also go through individual lawsuits similarly. From 1986 until 2017, the Army’s official policy prevented wearing Turbans and beards despite winning repeated religious liberty cases. (The Air Force did not change policy until 2019).

This is despite the 2015 Supreme Court case ruling about wearing a hijab, written by Antonin Scalia. “The rule for disparate-treatment claims based on a failure to accommodate a religious practice is straightforward: An employer may not make an applicant’s religious practice, confirmed or otherwise, a factor in employment decisions.” The 20th-century court precedents, written largely by protestants, that narrowly defined religious expression as explicit worship for non-Christians are now coming to impact Christians.

Much of the book’s value is pointing out cultural assumptions that lean to Christian benefit but which many will complain are about culture, not Christianity. The hiddenness proves her larger point (because the religious roots of the example have been lost or because the examples are simply not seen). I found myself arguing with her on many occasions. Still, regardless of any particular example, the weight of the number and range of examples makes the case well that there is Christian privilege.

The White portion of White Christian Privilege does matter, and one of the critical points is the discussion of intersectionality. She uses the phrase ‘one up and one down’ to talk about the difficulty in seeing privilege for those who have Christian privilege but are oppressed in other areas, for example, Black Christians who want to work for culturally appropriate public Christmas displays but do not see that the public Christmas display has its own privilege.

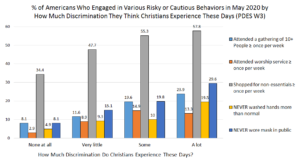

Right before I typed this up this morning, I saw this graphic in a tweet by Samuel Perry, sociologist and coauthor of Taking America Back for God.

The perception of oppression impacts how we act in the world and how we treat others. While it is mostly overlapping, a roughly similar percentage of White Evangelicals believe that Christians are more persecuted in the US than other religious groups, and White people are now more racially discriminated against than Black people are in the US. Those distortions matter, and I think books like this can help Christians see otherwise invisible privilege.

The book presents a ‘social-justice’ oriented model for addressing discrimination in the US. This is roughly similar to the type of antiracism that Ibham Kendi and others discuss regarding racial privilege and prejudice. I can see some reading this book and walking away dismissing not just Christian privilege but also racial and gender discrimination as well (several of the reviews on Amazon seemed to do just that). But at some point, we cannot orient ourselves primarily to those who are strongly resistant to issues of oppression but instead need to work on understanding and rectifying those areas. I know that will just prove the anti-social justice point for some. And I do want to bring about some level of common ground. But the common ground cannot come about at the expense of the oppressed. (See Race and Reunion by David Blight for an example of how that has gone badly in US history.)

White Christian Privilege: The Illusion of Religious Equality in America by Khyati Joshi Purchase Links: Hardcover, Kindle Edition, Audible.com Audiobook