Summary: American Christianity has slowly adopted a Jesus that looks and acts a lot like John Wayne, and that has distorted Christianity.

Summary: American Christianity has slowly adopted a Jesus that looks and acts a lot like John Wayne, and that has distorted Christianity.

When I first heard about Jesus and John Wayne, I had it connected to books on Christian Nationalism, like Taking America Back for God, maybe because that is how Matthew Lee Anderson framed his review in Christianity Today. That isn’t entirely wrong, but I am not sure it gets the main point of the book any more than framing it as an Anti-Trump book as this review does. The book opens with a vignette about Trump’s 2016 statement “I could stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoot somebody, and I wouldn’t lose any voters, OK?”

Jesus and John Wayne isn’t so much about Trump, or John Wayne, as much as it is about how since the 1950s, Evangelicalism in particular, and Christianity more broadly, has culturally embraced a concept of militant masculine Christianity, a ‘bad-ass Jesus’, as a central image for its discipleship and evangelism strategy. The movement to save America (yes Christian Nationalism is a component of the book), has been a reactive one. Whether it is communism (they are atheists, so the US needs to add ‘Under God’ to the pledge), or feminists (so we need to emphasize complementary gender roles and patriarchal authority), or loose sexual morals (so we emphasize purity and ‘kiss dating goodbye’), the point is that the Christian church in the post World War II era has not created a positive message of Christianity so much as looked at culture and done the opposite. Except when it hasn’t.

The ‘when it hasn’t’ is also essential. Because culture has embraced the individual macho man, whether it is John Wayne as the soldier or cowboy or the behind the scenes savior like Jack Bauer or James Bond, or the father with a very particular set of skills that will pursue his daughter’s kidnappers in Taken, the individual who can save us is part of the American mystique.

Jesus and John Wayne is a history book. It is tracing the 75-year history of the development of Evangelical conceptions of gendered leadership, which has resulted in widespread support of a president who does not match Christian theological or virtue ideals but is “somebody who is able to fight back” or phrased differently, ‘the US needs street fighters like @realDonaldTrump.’ The main focus of Jesus and John Wayne is the gendered conception of leadership and the way that the emphasis on exaggerated gender role divisions has distorted Christianity.

I am not going to trace the full history developed in the book. It traces the development of opposition of ERA and abortion, the embrace of Reagan (as an overt parallel to John Wayne) and his manly man soldier doing what needs to be done in Oliver North, the rejection of ‘softer’ parenting styles with James Dobson and the Pearls, Promise Keepers’ focus on men taking back leadership of the family, the later rejection of Promise Keepers as too tender and the embrace of ‘No more Christian nice guys’ and ‘spiritual badasses.’

What struck me most as a reader is how the progressive embrace of each of these steps was generally about either Evangelism of men outside of the church (because part of the emphasis was that if you evangelize men, you will get the rest of the family as well) or Christian renewal efforts inside the church. Part of what is outside the scope of Jesus and John Wayne, but has been explored in books like James KA Smith’s Desiring the Kingdom, or Mather’s Having Everything, Possessing Nothing or many others, is that discipleship can’t be mass-produced. Evangelicalism since the mid-20th century has attempted to use mass marketing tools, not just for evangelism but also for discipleship.

Jesus’ model of discipleship focused on individual and small group interactions. Discipleship is about a relationship with God, not information. When we turn discipleship into information sharing or cultural participation (Christian music, Christian books, Christian movies), we orient passive participation or intellectual assent without developing a deeper relationship with God or discernment about what it means to be like Christ. Part of what DuMez is pointing out in Jesus and John Wayne is the relationship between exaggerated gender roles and the embrace of authoritarianism. A traditional focus of discipleship is individual and corporate discernment of God’s will and leading, but authoritarian leadership styles prioritize following without independent discernment.

As I was reading Jesus and John Wayne, I kept thinking about Lauren Winner’s The Dangers of Christian Practice. The point of Winner’s book was that Christian practices are not unalloyed goods; they can be distorted and misused. Many within the post World War II Christian world seem not to have paid attention to the potential for Christian practices to be abused. I keep seeing comments like ‘we just need better discipleship.’ But the problems that are being pointed out by DuMez were caused by people trying to disciple Christians, not ignoring of discipleship altogether. While there were many Christians in the book that were hypocritically applying their ideas to others and not themselves (especially around sexual purity), I think virtually all of the leaders highlighted felt they were teaching rightly and were trying to serve Christ, even if they were also at times serving their own needs as well.

Where we go wrong is in our ability to discern what is right and what is not. As Christians, we will never come to complete agreement; universal agreement is not the goal. But it does matter that we seem to have adopted an idea that the means of accomplishing our ends are unrelated to the ends themselves. An easy example is tracks that are designed to look like money. The whole point of these tracts is that people will pick them up with the assumption that they have found a dollar bill, or a hundred dollar bill. But the means of tricking people into picking them up subverts the message that is at least in part about the truth of the gospel. Or in another example, from the book, the emphasis against sex, instead of teaching about the right use of sex, has ended up not just harming many couples’ actual sex life, but also wrongly located where responsibility for chastity lies. Also, the normative idea of men always wanting more sex than their wives has led to abusive understandings of women needing to ‘service’ their husbands as a means of keeping them happy and keeping them from having affairs and damaged both men and women outside of that narrative. Lost has been the discipleship around nuanced differences that take into account created differences or differences as the result of sin (trauma, rape, etc.).

Historically, there have been many examples of Christians taking into account blindspots without discounting the Christianity of others that had blind spots. CS Lewis’ introduction to On the Incarnation by Athanasius has a classic defense of reading old books, not because old books are better but because they have different blind spots. Ignatius, in his Rules for Discernment, talks about how Satan can appear as an angel and how we are not aware of the harm that we cause others. Both are aspects of how we, as Christians, need not only discernment but also a community to help us see more than what we can see individually.

Part of why I am training to become a Spiritual Director is that the history of the practice has been designed to help individuals seek God’s will, listen together to God’s direction to develop a shared discernment, and to appropriately individualize discipleship because we are uniquely created by God. It would be easy to try to create a program to get every Chrisitan into spiritual direction and create a movement to shepherd Christians into growth. But movements often fail, and we have already seen a shepherding movement fail spectacularly.

The end of Jesus and John Wayne was the most critical chapter in the book for me. There was almost no movement or group detailed in the book that I was completely unaware of. There indeed were more details provided than I knew, but the end of the book pulls out the characters of the story that had been told up until that point, and one after another lays out their falls from grace. In many cases, there were no significant ramifications for pastors or leaders. Those leaders had consensual affairs, raped employees or church members, covered up rape or child abuse of others, abused their organizational power or authority, misused funds, destroyed their or other’s families, demeaned the name of other Christians (or non-Christians) falsely, or other sins. Cases where pastors called out a particular sin, but then engaged in it, or allowed it when convenient were common. Yet another famous pastor mentioned in the book was called out yesterday on twitter for condemning all divorce, even in the case of physical abuse, blessed his son’s second marriage. The point of the tweet wasn’t that the son was wrong for marrying again, but that the grace offered to him was not present for others (and continues to be taught.)

Edward Glaude Jr, in his book, Begin Again, discusses Princeton’s forced movement toward discussing the complicated history of its relationship to President Wilson. Wilson was both former president of the United States and Princeton University. Princeton, like all institutions, does not like complicated history. But the only accurate history is a complicated history. Glaude rightly notes that “Who and what we celebrate reflects who and what we value.” Simplified history, a celebratory history where there should be a lament, denies the full humanity and participation of the imago dei of those who are lamenting. A militant masculine Christianity not only overvalues a particular expression of Christianity that should not be valued, but it also diminishes an expression of the body of Christ, which needs to be heard to be a balanced body. The distortion of the church has happened in part because it hasn’t taken the whole body of Christ seriously in developing its theology and orthopraxy.

The church is just messy. It is made up of sinful humans, and as I frequently say, the problem within Christianity that most shakes my faith isn’t the problem of evil, but the lack of change and growth among people that claim to be followers of Christ. Eugene Peterson’s book Practice Resurrection emphasizes that the only way that we can grow in Christ is to be surrounded in community among other Jesus followers that are still sinners (as we all are). That does not make the problems of sin within Christianity any less critical. If anything, it shows the need for books like Jesus and John Wayne more. Part of what Ignatius points out in his discussion of spiritual growth is that the repression discussion of sin and temptation can empower it. And that bringing sin into the light so that it can be openly dealt with is the easiest way to break its hold on our lives. The continued pattern of Christians covering up sin is not only a violation of Christian teaching around sin, but it is the best way to ensure that Christians’ reputation will suffer because hidden sin grows.

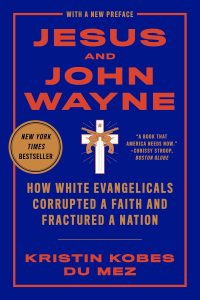

Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation by Kristin DuMez Purchase Links: Hardcover, Kindle Edition, Audible.com Audiobook

Adam, as always, your insights are fresh and provoke painful but needed assessment.

Thank you for permission to post a few quotes on Discipleship.Newtwork

You are always free to reuse what you want Phil.