Summary: The biography of Richard Allen, the founder of the African Methodist Episcopal denomination and one of the early Black leaders in the US.

Summary: The biography of Richard Allen, the founder of the African Methodist Episcopal denomination and one of the early Black leaders in the US.

Many people may be slightly aware of Richard Allen, but not much about him. At least that describes me and why I decided to pick up Freedom’s Prophet. This quote from the introduction sets the stage for why Richard Allen is important.

“Allen did not live through these immense changes passively, a black man adrift in a sea of impersonal and malevolent forces. Rather, he shaped, and was in turn shaped by, the events swirling around him. As the most prominent black preacher of his era, he helped inaugurate a moral critique of slavery and slaveholding that shaped abolitionism for years to come. As one of the first black pamphleteers, he pushed not only for slavery’s demise but also for black equality. As a black institution builder, he spurred the creation of autonomous organizations and churches that nurtured African American struggles for justice throughout the nineteenth century. As a sometime doubter of American racial equality, he participated in black emigration to Haiti. As a leader of the first national black convention, he defined continent-wide protest tactics and strategies for a new generation of activists. Bishop Allen’s lifelong struggle for racial justice makes for a compelling and illuminating story—a tale about a black founder and African Americans in the early American republic.” (p5)

Richard Allen was born into slavery in 1760 and lived until the age of 71 in 1831. Like many who were enslaved, his family was split apart and sold as a child. He became a Christian through the work of early Methodists, who welcomed Black participation in the church. At 17, he joined the church and started to evangelize and preach. Through his preaching and evangelism and the preaching of a white abolitionist preacher, his owners became convinced of the evil of slavery. But his owners did not simply free him and others who were enslaved; he allowed them to buy their freedom. Richard Allen bought his freedom for the equivalent of about five years’ wages for an average laborer by age 20. When he was 24, he was officially ordained and spent two years as a circuit-riding preacher before becoming one of the ministers at St. George’s Methodist Episcopal Church.

There, he and Absalom Jones were famously removed from the church for not sitting in a newly segregated balcony during the service. Eventually, Absalom Jones started a new Black Episcopal church (remaining in the predominately white denomination). In contrast, Richard Allen started a Black Methodist church, which eventually withdrew from the white Methodist denomination and started the first Black denomination in the US (African Methodist Episcopal).

This biography is well worth reading to know more about Allen as an example of a very early formerly enslaved abolitionist writer and preacher. But I also think it is worth reading as an example of how the intransigence of white attention to racism often impacts Black and other minority Christians who appeal to white Christians theologically. I am going to use a few quotes to show that shift.

“As his antislavery sermonizing and pamphleteering efforts illustrate, Allen adhered to the principles of nonviolent protest throughout his life. Even in an age of great slave revolts, from Gabriel’s Rebellion in Virginia to the Haitian Revolution in the Caribbean, Allen’s ideology was perhaps the norm. Most slaves in the Atlantic world did not, and could not, successfully rebel; most enslaved people had to endure. But what did that actually mean? For Allen and black founders, it meant turning nonviolent protest—enduring over the long haul—into a moral and political weapon.” (p10)

“At the heart of Allen’s moral vision was an evangelical religion—Methodism—that promised equality to all believers in Christ. Indeed, one of Allen’s best claims to equal founding status was his attempt to merge faith and racial politics in the young republic. His constant sermonizing on slavery’s evil was (in theory) perfectly pitched to men and women who viewed faith as a key part of the American character.” (p23)

“A former slave now in the capital of free black life, Richard Allen publicly challenged Franklin’s line of thinking. The problem, he commented in 1794, lay not in blacks’ essentially subversive nature but in white society’s consistent failure to nurture African American equality. Allen condemned not only slavery but also the racialist beliefs underpinning slavery and black inequality. He then proposed his own solutions in very Franklinesque language. Whites, Allen suggested, might try the “experiment” of treating black people as they would members of their own family. Next, he wrote in an almost direct reply to Franklin’s fears of black equality, white citizens must believe in their own Christian and republican language. It was a message he returned to again and again: liberate blacks, teach them scripture and principles of good citizenship, and watch them become pious and respectable members of the American republic.” (p25)

“As Richard Allen later put it in a famous letter to Freedom’s Journal, America was a black homeland precisely because of slaves’ and free black laborers’ incessant toil for the country’s prosperity and independence. “This land which we have watered with our tears and our blood,” Allen proclaimed, “is now our mother country.” African Americans deserved the full fruits of citizenship.” (p150)

“Perhaps the most intriguing aspect of Allen’s and black founders’ activism, then, was their increasing cynicism about achieving racial justice in America. By the second decade of the nineteenth century, Allen grew so doubtful that he flirted with various Atlantic-world emigration plans. No fleeting consideration for him, Allen meditated on black removal for the last fifteen years of his life. He supported black-led African-colonization schemes before becoming one of the most forceful African American proponents of Haitian emigration. America, he told Haitian president Jean-Pierre Boyer in 1824, is a land of oppression, whereas the great black republic of Haiti promised “freedom and equality.”43 Allen even headed the Haitian Emigration Society of Philadelphia, helping hundreds of black émigrés set sail for the Caribbean. Still later, he supported emigration to Canada.” (p19)

Early in his preaching, Richard Allen worked with and was friends with the first Methodist bishop in the US, Francis Asbury. That early partnership gave Allen hope for white support of abolition. However, his experience with increasing segregation (St George was not segregated when he first became a pastor, and residential segregation did not exist yet in Philadelphia) discouraged that initial hope. Early abolitionist societies did not allow Black members, and throughout his life, he was not officially a part of any abolitionist groups that were not black-led. Methodism preached a structured moral uplift message, which fit Allen’s personality and drive. The early 19th century had a hardening of the racial caste system, and white supremacy (in the sense of a biological or cultural racial hierarchy) became culturally dominant throughout the US. Allen became well known and fairly wealthy for the time, but as the population of free Black residents of Philadelphia grew, white racial attitudes hardened, and overt segregation increased so that the opportunities that Allen had were more difficult for younger free Black Philadelphians.

In the early 19th century, most white abolitionists were solidly white supremacists who did not believe that free Black people should remain in the US. Much of the white abolitionist work assumed that free Black residents of the US should be removed from the US, preferably back to Africa. Initially, Allen also supported “colonialization” efforts for different reasons. His struggle with white Methodist control of his church and his work to move it to Black independent control led him to think that moving to Africa may be the only way to have autonomy. However, the members of his church and the Black community of Philadelphia opposed colonialization, and eventually, Allen stopped supporting African colonialization, although he did still support moving to Haiti after it gained its freedom and then later Canada after the initial efforts to move to Haiti failed.

Allen did not give up on his efforts for interracial cooperation, moral uplift, Black education and training, or Black political, economic, and religious autonomy. But in many ways, the reality of Black life grew worse, not better, for the vast majority. Allen did everything “right,” and white Christians, even those who were relatively liberal on racial issues, disappointed him.

Freedom’s Prophet is not hagiography. Allen could be difficult to work with, and his life had plenty of controversy. There was a church split, the already mentioned pushback on colonization, accusations of money mismanagement (which do not seem true), and other examples of frustration and human limitation. I think of him as somewhat similar to Howard Thurman’s position toward the Black freedom struggle. Richard Allen was important as the founder of the first Black-led denomination, the first significant Black printer and pamphleteer, an advocate of moral uplift and non-violent protest, and a mentor. But the fruits of his efforts were largely felt after his death. A new generation of abolitionists, both white and Black, arose toward the end of his life and after his death. William Lloyd Garrison did not start the Liberator until the year of Allen’s death, and Frederick Douglass did not escape slavery until eight years later. The Civil War started just over 30 years after his death. But Allen’s efforts were essential to those later efforts.

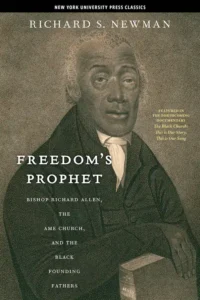

Freedom’s Prophet: Bishop Richard Allen, the AME Church, and the Black Founding Fathers by Richard S. Newman Purchase Links: Paperback, Kindle Edition, Audible.com Audiobook

1 thought on “Freedom’s Prophet: Bishop Richard Allen, the AME Church, and the Black Founding Fathers by Richard S. Newman”