Summary: Part memoir, part encouragement for emotionally healthy activism, part grace for the journey.

Summary: Part memoir, part encouragement for emotionally healthy activism, part grace for the journey.

I have been blogging through my reading for about fifteen years now. One of the things I still am uncomfortable doing is writing about books where I have more than a passing acquaintance with the author. I do not want to oversell my relationship with Ally Henny, but I volunteered on a project she led for years. I am part of a group chat that, while it was well established before Covid, became part of my covid lifeline. I read some early portions of I Won’t Shut Up, and I am mentioned in the acknowledgments. But we have never met in person (like many social media acquaintances), and I don’t want to pretend we are best buds. It is this type of relationship that makes it hard to write, not because I don’t like the book (I really do like and recommend the book), but because I am trying to figure out how to write about a book I like while acknowledging the reality of my bias is just a tricky balance to do well.

The best I can do is describe why I Won’t Shut Up adds to and differs from the many memoir-ish books about racial issues in the US. First, I think that her writing as a Black woman who grew up and has primarily lived in the rural Midwest is something that no other books I have read has centered. Setting and context matter, and different backgrounds lead to different insights.

Second, there is a thread of grace throughout the book that is helpful for books like this. She has grace for herself and the ways she has grown over time. She has grace for those who have harmed her and those around her. And she has grace for the readers she is trying to encourage to grow. That doesn’t mean that she ignores the harm, but that she has grace for the potential for change. She stayed with a church for a long time, which was harmful. She gave the benefit of the doubt and kept trying to help that church, and particularly the pastor of that church, see areas of weakness. But as she concludes, leaving sometimes is necessary. And when she eventually leaves that church, she has grace for the grief that she and her family feels.

The third aspect that I commend, which may not be quite as unique, is that Ally Henny frames this book around discovering her voice and how that voice is essential to moving forward as a country. Other books like Raise Your Voice: Why We Stay Silent and How to Speak Up by Kathy Khang and I’m Still Here by Austin Channing Brown both talk about how the voice (metaphorically and in reality) is essential to truth-telling. And without truth-telling, there can be no way forward. This is why, so often, it is Black and other minority women who are marginalized for speaking out about oppression.

When it was available, I pre-ordered the Kindle Edition. But I knew as soon as she announced it that I would primarily listen to the audiobook because the theme of her voice would carry through more clearly in the audiobook. Having read some early drafts of the chapters, I knew there were accounts of spiritual harm. I don’t want to equate anything in this book to what I have experienced, but I have been grieving leaving my own church, and I was reluctant to read the whole book when it came out. This book is consciously written for Black women, but the particularity of it makes it helpful to understand experiences that I do not have. I hope that I am not reading in an unhelpful “white gaze” type of way but in a way that honors the fact that I have something to learn.

Several of the characters are not fully named. One of those is “Pastor______.” As a fellow white male, one of the problems of Pastor_______ is that he seems not to understand that he, too, has something to learn from those around him, particularly Black women. Dr Willie Jennings’ book After Whiteness is particularly about theological education and how it has traditionally taught pastors to be “self-sufficient masters of educational knowledge.” Pastors who always understand their role to be the leader and expert have no place in their understanding of how to learn from others. I have no idea of the educational background of Pastor______, but I do understand the impulse to want to master the knowledge and tasks around me.

There is grace in the book for slow learners. But part of what I think is important (as a 50-something-year-old white man) is that one of the most important things we can do for our legacy is to orient our lives to dealing with our own baggage and, at the same time, turning over our need to be in charge because the way forward is only through repentance and empowerment of others. Overwhelmingly, multi-ethnic churches, as the one which was led by Pastor______ are led by white men. According to research by Barna and Michael Emerson, roughly 70% of all multi-ethnic churches are led by white men. While the number of churches that can be classified as multiethnic has roughly doubled since Divided by Faith came out, the number of white men leading multi-ethnic churches is increasing, not decreasing. And while there are pastors who are doing well leading multiethnic churches, many people I know, have left those white-led multi-ethnic churches because of the harm they have felt there. (Korie Edwards also has written well about this.)

It was Ally who started the #LeaveLoud movement. No church is perfect, but some churches are definitely less perfect than others. Part of this less perfect reality is that the very people who need to be leading because of their orientation toward healing and harm mitigation, are some of the people who are least likely to be followed. Bias toward what we think of as leaders, means that white people tend to want to have white leadership. And a lot of Black or other people of color know that and end up in white-led multi-ethnic churches. There are no simple answers here, but that orientation is going to have to change. I Won’t Shut Up is part of that movement toward change.

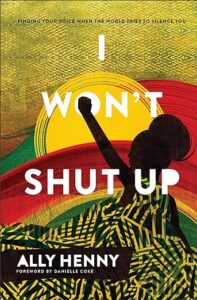

I Won’t Shut Up: Finding Your Voice When the World Tries to Silence You by Ally Henny Purchase Links: Hardcover, Kindle Edition, Audible.com Audiobook