Summary: How do you summarize a life like John Lewis’?

Summary: How do you summarize a life like John Lewis’?

I am not new to the story of John Lewis, but this was the first full-length biography I have read about John Lewis. I have previously read the graphic novels (The March Trilogy and Run) and the short biography by Jon Meacham, as well as watching the documentary Good Trouble. And Lewis figures prominently in many biographies, memoirs, and Civil Rights era histories. But I had not read a full-length biography.

David Greenberg has previously written biographies of Nixon and Coolidge and two books about the presidency. This is a biography that used hundreds of interviews and personal papers. And I think perhaps most interesting to me is that the biography was only half finished when Lewis was ousted from SNCC. The main difference is that everything I have previously watched or read primarily focused on Lewis’ early civil rights work prior to leaving SNCC.

“Lews found himself, at age 26, with no job, unmarried and unsure what to do with his life. The movement to which he had devoted his adult life was veering away from the ideals that had animated it. To remain in the struggle, he would have to find another path.”

Part of what has always previously struck me about Lewis was how young he was when he was thrust into leadership. He was a leader of the Nashville Student Movement before he was 20. He was one of the speakers at the 1963 March on Washington when he was 23. Stokley Carmichael replaced him as chairman of SNCC when Lewis was 26. Everything I had previously read about Lewis was how his orientation toward a belief in nonviolence as a principle, not just a strategy paired with his maturity as a young man. He was not inclined to date or drink or parties, but he did draw people to him.

That early fame did not just lead to an easy later life. He successfully led the Voter Education Project for seven years. Under his leadership, VEP registered more than 4 million people. He also served for short periods for a foundation and then in the Carter administration supervising the VISTA program. Eventually, he moved back to Atlanta after a time in New York and Washington DC.

A bit over two years after leaving SNCC Lewis married Lillian Miles. Lillian was a librarian and an important figure in his later life. But they spent significant time apart. Lewis was used to traveling with his work for SNCC and continued to travel for his various jobs. In 1977, Lewis first ran for Congress but lost the primary. Over the next year, there were many changes. He had resigned from the VEP to run for Congress. The couple had adopted a son in May 1976. In June, he was offered a job as Associate Director for ACTION, an umbrella agency that included Peace Corps, VISTA, and other programs. In July he was confirmed by the Senate. Lillian and their son did not move to Washington DC with him.

Lewis did not agree with Carter on many issues and resigned before the end of Carter’s term and ran for Atlanta city council. The city council job was officially part-time with part-time pay. And they lived mostly on Lillian’s salary as a librarian. Lewis served in the city council for seven years, primarily acting as a conscious against corruption and against development projects that would break apart communities. This included opposition to the original plans for the Carter Center.

In 1986, Lewis again ran for the 5th Congressional District, this time against Julian Bond, one of his friends from SNCC days. That was a brutal campaign, one that split the friends for the rest of their lives. But Lewis won and served the rest of his life in Congress rising to senior leadership within the Democratic delegation.

Part of what I appreciate is that while Lewis is honored in the book, he is not lionized inappropriately. He had weaknesses. He maintained his position as conscious of Congress, he took difficult stands, and not all of them were wise stands looking back on history. He had weaknesses as a leader and manager. But he was not prone to some of the ways that leadership, power, and money tend to become a problem for many. He was still largely an everyman, even as his fame grew in later years.

The March Trilogy and earlier books that he worked on (usually with a secondary author who primarily did the writing) increased his fame. Because so many civil rights era figures passed away young, either from violence or health issues that were often impacted by stress and violence, Lewis became not just a figure of history for the civil rights movement, but also a visible symbol of the movement. Lewis’ work to commemorate the Selma March, including bringing annual delegations from Congress to the march, and his work to get the African American History Museum approved and built were some of the most significant work he did while in Congress. Lewis used his history to remind Congress and the country of the struggle for equality that was not so long ago.

I think the most significant weakness of the book was a lack of attention to his faith and the way it shaped his life and thinking. Greenberg does not ignore Lewis’ faith, but it isn’t a significant theme of the book. I think Lewis would be a good subject for Eerdman’s Library of Religious Biography series.

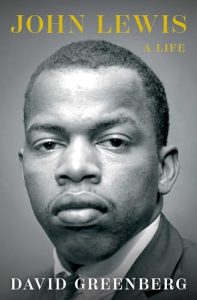

John Lewis: A Life by David Greenberg Purchase Links: Hardcover, Kindle Edition, Audible.com Audiobook

3 thoughts on “John Lewis: A Life by David Greenberg”