Summary: A discussion about how the rise of independent celebrity authors, pastors, speakers, musicians, and churches is a problem, not just because of abuse and a lack of accountability, but also because our culture is more focused on celebrities for their own sake.

Summary: A discussion about how the rise of independent celebrity authors, pastors, speakers, musicians, and churches is a problem, not just because of abuse and a lack of accountability, but also because our culture is more focused on celebrities for their own sake.

In some ways, Celebrities for Jesus is a book that I am not sure why it needed to be written. I say this not because it isn’t worth reading or because it isn’t a good book, but because much of the main point should be self-evident. I think we should know that as churches are more focused on the size and celebrity of their pastors, this will create a harmful culture, even if there is no overt abuse or harm. It should be clear that when a church is centered around a well-known leader, the church is not primarily about Jesus but about the leader. (Or the will of the leader is assumed to be the will of Jesus.)

In my life, I have been exposed to many megachurch leaders. Like many, I have read many books and watched many sermons by those leaders. But I have also been involved in small closed-door meetings with some megachurch pastors. And honestly most of those in the meetings are no longer in leadership. A few retired without scandal. But many, including James MacDonald and Bill Hybels, who are both profiled in the book, had significant scandals, and that scandal felt to me like it was just a matter of time from when I met them in the early 2000s. I also spent years as a member of a mega church without significant scandal, and in deciding to leave that church, the issue of celebrity was involved because it felt to me that the church was making decisions to continue to center the pastor in ways that made me concerned for the long term future of the church.

Despite my somewhat facetious question about why the book was written, it is helpful to think about what has shifted. Part of the early book is about the difference between fame and celebrity. I am oversimplifying here, but fame is about being well-known for a position, talent, or product (being a good writer, speaker, or musician). But as Beaty describes it, celebrity is a shift from being famous for what you have done to being known for being known. Celebrity, especially with the rise of social media and mass media, means we have a false “illusion of intimacy while drawing our attention away from the true intimacy available within a physical community.” Said more simply, Beaty says that the summary of the problem of celebrity is “social power without proximity.” Not only do celebrities influence us without us actually knowing them as a whole person, but in some sense, we do not want to know them as a whole person because to know someone as a whole person would break the illusion of intimacy and perfection that we have of celebrities.

Read more

Summary: A very fictionalized retelling of Lady Jane Grey’s marriage and assent to the throne with magic.

Summary: A very fictionalized retelling of Lady Jane Grey’s marriage and assent to the throne with magic.

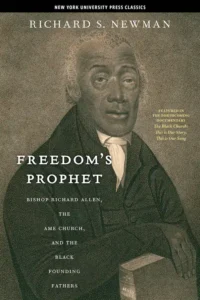

Summary: The biography of Richard Allen, the founder of the African Methodist Episcopal denomination and one of the early Black leaders in the US.

Summary: The biography of Richard Allen, the founder of the African Methodist Episcopal denomination and one of the early Black leaders in the US.  Summary: An exploration of Quaker practices of group discernment in an academic or research setting.

Summary: An exploration of Quaker practices of group discernment in an academic or research setting.