Summary: A brief memoir about how Gushee’s attempt to follow his calling moved him out of Evangelicalism.

Summary: A brief memoir about how Gushee’s attempt to follow his calling moved him out of Evangelicalism.

David Gushee is one of those authors that I know about but until I read his book Changing Our Mind, I do not think I had read more than a couple articles by him (mostly at Christianity Today.)

The transcript of a speech at the end of the 2nd edition of Changing Our Mind (the 3rd edition is now out) is what made me what to pick up this book. Gushee’s dissertation was about German Christian response to the Holocaust. Gushee in his speech drew parallels to how ethical thinking was impacted by the understanding of actual people harmed.

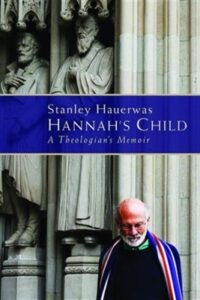

Last week I saw that this memoir was coming out. I picked up a review copy and moved it to the top of my reading list. I have been craving memoirs of my elders lately. After finishing the four volumes of Madeleine L’Engle’s memoirs I was intending to pick up Stanley Hauerwas’ memoir Hannah’s Child. Gushee’s memoir jumped in line.

Seeing how people work out their faith over time, in good and bad times, is very encouraging. And watching how people of deep faith come to different conclusions in their theological and ethical positions while retaining a robust devotional and theological life also is a good reminder of the greatness of God, and of our own limited perspectives.

David Gushee grew up a nominal Catholic. As a teen, Gushee came to faith through a Southern Baptist church in Northern Virginia. Quickly feeling the call to ministry, he went to undergrad at William and Mary and then seminary at Southern Seminary. Gushee had not been prepared for the internal politics of the SBC that was in the throes of a significant theological battle.

He moved from Southern to Union Seminary in New York City, from a school that was fighting about how conservative to be, to one that was the center of Liberation Theology. For three years on campus and then three years off campus, he started to gain an understanding what it means to be too conservative for the liberals and too liberal for the conservatives.

Read more

Summary: Historical fiction imagining the Underground Railroad, as an actual Railroad.

Summary: Historical fiction imagining the Underground Railroad, as an actual Railroad.

Summary: Gamache, now head of the Sûreté du Québec gambles.

Summary: Gamache, now head of the Sûreté du Québec gambles.